Called to Serve

The Story of Khaibar Shafaq, Afghan Evacuee

Part I: Evacuation

Aug. 29, 2021. Kabul, Afghanistan. 2 or 3 a.m.

As the vehicle carrying Khaibar and his companions moved closer to the Kabul International Airport, through the early morning darkness Khaibar could make out the shadowy outlines of a crowd of people surrounding the road ahead. His stomach dropped. How were they going to manage to get through the crowd, close enough that he could speak with one of the U.S. Marines?

It was their fourth middle-of-the-night attempt to enter the airport. Over the span of the last two weeks since the Taliban invasion of Kabul, Khaibar had arranged with the U.S. embassy via phone to bring his group of companions seeking to evacuate to the airport checkpoint manned by U.S. Marines. They’d told him where to come and when to meet – usually in early hours of the morning. But each time they’d gotten close to the checkpoint, the group had been met with a crowd of thousands of people blocking the way, as Taliban forces intercepted cars.

It had been chaos, madness – desperate families, dragging babies and suitcases, pushing through the darkness to try and get through to the airport. There had been looting, beatings of civilians by Taliban forces, shots fired – forcing Khaibar and his group to abandon their attempt each of the previous 3 times.

His heart started beating faster. They had to get through this time – they were running out of time. The U.S. forces were going to leave the country in a matter of days; the evacuation was winding down.

Khaibar told his friend to stop the car. There was no way they would get close enough unless they went on foot. He told his group – about 8 people – to follow him, and they pushed forward in the crowd.

They made it almost a mile, until they were close enough that Khaibar could make out a low barbed-wire fence, around 3 feet high. They could see the airport checkpoint where U.S. Marines and the Afghan soldiers of the fallen government were verifying documents of those who had managed to push to the front of the crowd. But they were still so far away.

Khaibar told his companions to wait near the fence. He was going to try and jump over it in order to speak to the U.S. Marines. He knew that few people in this crowd had the necessary paperwork and credentials to be part of the evacuation – but he and his companions did. They had to make it through, and this felt like their only chance.

With a rush of adrenaline he ran forward and jumped, landing on the other side. He hardly had time to take a breath before Afghan soldiers were running toward him, their guns aimed at him, shouting to go back or they would shoot.

Heart racing, he shouted out his story, in as calm a voice as he could muster.

“Please, I am acting under the direction of the Marines who told me to come and find them. I work for an American organization and in my group there is an American citizen. If I could just speak to a Marine, please, sir…”

“This is your final warning. Get back behind the fence!”

They began roughly pushing him toward the fence, but at that moment a U.S. Marine turned and approached them.

“Wait. I’ve seen this man before. You are Khaibar Shafaq?”

“Yes, sir.” Khaibar fought to keep his voice from shaking.

“You work for MercyCorp and the Red Cross?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Where is the rest of your group? Do you have your documents?”

“Yes, sir, I have them, and my group is on the other side of the fence, if I can go get them…”

The Marine told the soldiers to release Khaibar. They let go of his arms; with effort he regained his balance. The Marine told Khaibar to point to point to his companions, which he did.

Khaibar’s companions were allowed to pass to the front of the checkpoint. They entered the fenced area and followed the Marine with his flashlight past the barrier of the checkpoint and behind a low, concrete partition wall. They were told to sit down and wait there. The Marine collected from each of them a packet of identifying documents, then turned to leave.

“Wait, sir?” Khaibar called after him.

“Yes?”

“What are we waiting for? Are we safe here?”

The solider nodded. “We will review the credentials of those in your group. You’ll be safe here. You’re under the protection of the U.S. government. We’ll be back soon.”

Khaibar turned back and slunk down against the wall. He repeated the assurances of the marine to his companions, there were some murmurs of shared, exhausted relief, and then they fell into silence.

He put his head back against the cool concrete and took some deep breaths as his racing heart slowed. Sweat was pouring down his forehead. As they waited Khaibar’s mind whirred but could hardly process the events of the last hours, not to mention the last few weeks.

Khaibar, a disaster relief specialist working for MercyCorp, an American humanitarian organization, had known for months that he would soon become a target of the Taliban regime, which had been slowly capturing the country city by city, headed for the capitol, as U.S. forces withdrew. Two months ago he had moved his family – his wife and 3 young children – out of the country, to Istanbul, where he’d gotten them 2-year visas and rented a small apartment.

Fifteen days ago, he had boarded a plane to Kabul to resume his job after an agonizing goodbye with his family. The sound of his kids’ wails as the elevator doors closed behind him on his way out of the apartment building haunted him. There were only 6 other people on his flight back to Kabul, as most others were fleeing the city. He’d returned to his apartment and slept, expecting to go into work the next day.

But the next morning, Taliban forces surrounded and then captured the capitol.

He woke up to the sights and sounds of the invasion – empty Afghan police vehicles in the road, trucks with white Taliban flags, looting of shops, shouting. He stayed in his apartment and promised his frantic wife on the phone that he would do his best to make it out. He gathered friends – mostly others with American connections, including one American citizen – to his apartment while they tried to contact the U.S. embassy and reach the airport for two endless weeks. After each of the previous 3 failed attempts, they had returned to the apartment, despairing, but soon they resolved to try again. And now here they were, some of the lucky few to have made it past the checkpoint, possibly on the brink of safety.

Over the next hour the Marine returned with a few more groups of people, who sat down beside Khaibar’s group against the wall. Then, when there were about 30 people, the Marine approached Khaibar and asked him to translate for the group.

At the Marine’s direction Khaibar instructed the group to climb into army trucks. They were taken closer to the airport. As they entered the doors they were met by another dizzying scene of thousands of people milling about, slowly forming half-hazard lines which ended at groups of Marines who were trying to register those present and put names into databases.

Given his excellent English, Khaibar was quickly enlisted to help with the effort to organize the throngs of people into groups that would fit onto 10 planes departing that day. Each plane had a capacity of around 500 people.

With years of experience in crowd control and disaster relief, he leapt into action.

With a megaphone he shouted instructions to the crowd, and gradually they began forming the appropriate lines. He helped the Marines take down information and passed out water. Everywhere about him were people with determination, confusion, fear, and exhaustion on their faces – mothers and fathers, little ones, the elderly and infirm. They carried their most precious belongings in their arms, in backpacks and overpacked suitcases.

Hours later he was aboard one of the planes, wearing a headset and speaking instructions to the 500 people aboard the aircraft over the intercom. They were seated in rows on the ground, including children and dozens of heavily pregnant women, but Khaibar kept having to pass on the instructions to get up, move back, squeeze closer together.

It was inhuman, these conditions — the heat, the noise of the crowd; the overhead lights; the scarcity of food, water, and bathrooms — but like every person aboard the plane, his only thought was survival. They had made it this far; they could survive this.

Then, before he knew it, the plane was accelerating. They were in the air.

Amid the din of the engine Khaibar’s mind flashed to his homeland in the mountainous north of Afghanistan, to his brothers and sisters still living there, his friends, his office, his house. He thought of his children, and his wife, Zuhal, alone in Istanbul. When – if ever – would he see these beloved people and places again?

Then he pushed the thoughts away. They were too hard; he couldn’t grieve now. He could only focus on the present, where he was, for now, on his way to safety – first to Germany, then to the United States.

Part II: Arrival in the United States

Fort Pickett, Virginia

October 2021

Khaibar sat alone at a table in the recreational room at Fort Pickett military base in Northern Virginia. In his hands he was fiddling with a phone – his friend’s – trying to get it to connect to the dim WiFi in the rec room. But there were a few dozen other people in the room trying to do the same thing, all competing for this lifeline connecting them to the people they’d lost in Afghanistan.

It had been a long morning at the base. Khaibar had been there for two months now at the military camp in Virginia with thousands of other Afghans who were being processed for resettlement around the United States. They lived in crowded barracks and ate meager food. They interacted with doctors, case workers, and other government agencies working to get them ready for resettlement. They anxiously and restlessly awaited news from their family members back in Afghanistan, comparing among themselves what they had heard.

This morning, like every other one, Khaibar had been helping keep order in the camp and translate between the government staff and his fellow Afghans. He had helped break up arguments between residents, ensured orderliness at meals and clinics, and helped people fill out paperwork. He tried to be as useful as possible – which helped the days go by faster, and kept his mind from incessant worrying about his family, both back home in Afghanistan, and in Istanbul.

Suddenly the phone connected to the internet. Messages from his family started pouring in as he signed into Whatsapp. He found his wife’s contact and dialed.

Then he heard a “Hello?” in his wife’s voice, and emotion flooded him – relief and joy and painful longing. He had not heard her voice in over 2 months; this was the first time he’d gotten access to a phone.

He choked back a response and wiped tears from his eyes. He asked if he could see the kids. They tried a video call, and then their beautiful faces were all there on the screen — his 11 year old daughter, and his two sons, aged 7 and 5.

They all cried, and beamed through tears, then tried to exchange information as the three kids voices piped different pieces of news, some more serious and others lighthearted. They talked for over an hour, with the video cutting in and out.

Later, when he knew the kids were asleep, he called his wife again.

“Zuhal, I can try to come back,” he said. “I can try to make it to Istanbul. I don’t want to leave you all alone there, and I don’t know how long it will be until I can bring you here.”

“No,” she said through tears, “you have to stay. There is nothing for us here. The children need a future. We will wait as long as it takes.”

The thought of her alone with the kids in that city filled him simultaneously with rage, grief, and helplessness.

“I will do everything I can to bring you here as soon as I can.”

In the next few weeks, Khaibar spoke to his family every evening for over an hour. He quickly realized that talking about their daily situation was unbearable for all – so instead, he taught his children, especially his 11-year-old daughter, English. He gave them activities and homework assignments and quizzed them.

They laughed and joked, and that hour became a small light in each of their days.

Western Kentucky

2 Months Later.

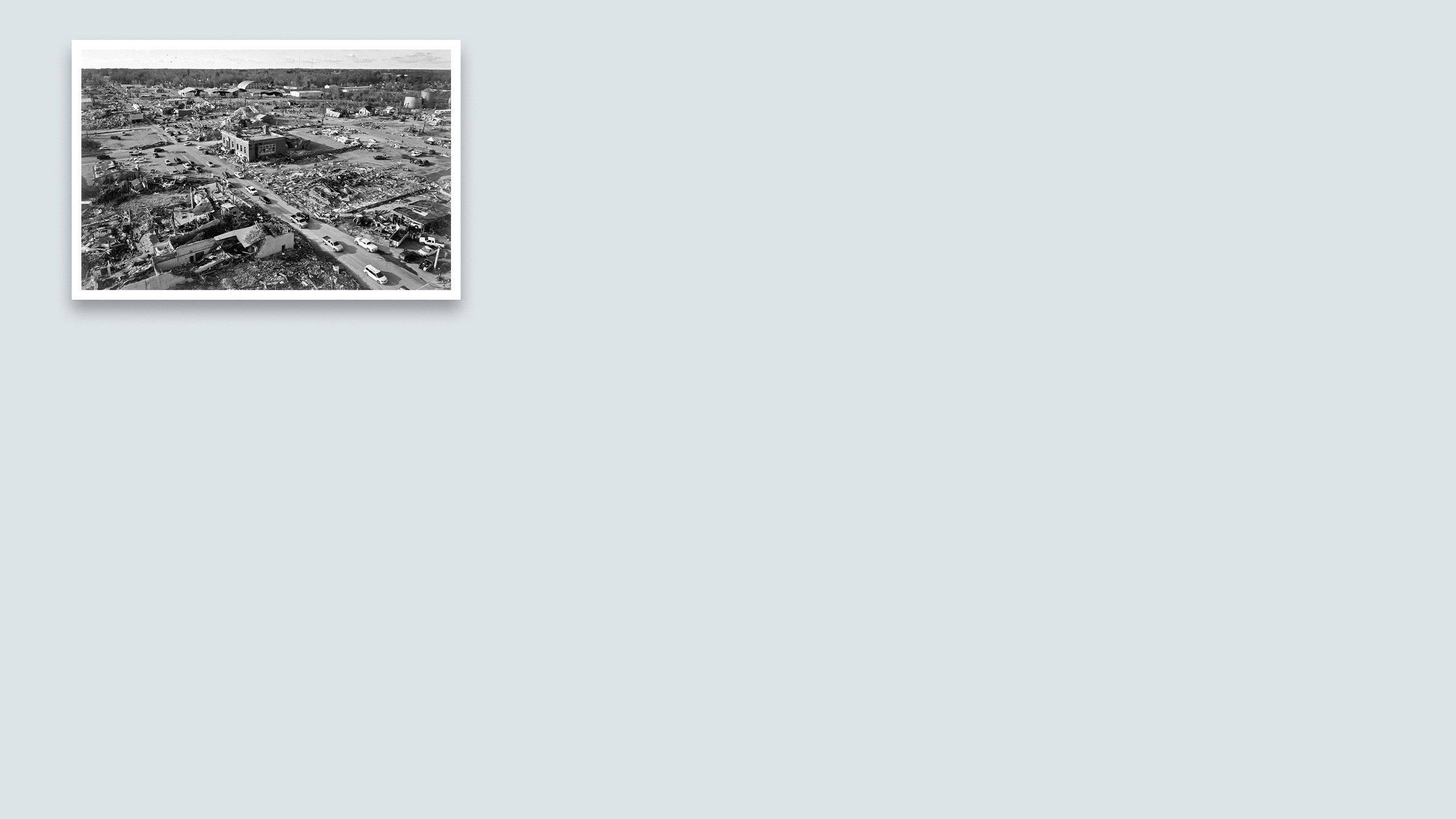

Khaibar stood still in a muddy driveway, surveying the devastation. For a few moments his mouth hung open. He was speechless, horrified – in all his years of disaster work, he had never seen anything like this.

Where there had previously been 20-30 homes were now sprawling piles of wood, broken furniture, and debris. The tornado the previous evening had swept through the plain, wrecking all in its path. The devastation stretched on for miles – trees and powerlines down, homes ruined, lives ended and upended.

He turned to Susan, the director from Catholic Charities standing next to him, and they began conversing about what to do. After they made a plan and list of which homes to attend to first, which people they needed to immediately speak with, he turned to her with a dry smile.

“Susan, I think I know why God has brought me to Owensboro,” Khaibar said.

“Yes,” she replied quietly. “Yes, I think so, too.”

Khaibar had arrived less than a month ago to Owensboro, Kentucky, the small southern city where he’d been assigned for resettlement. He and his close friend from Afghanistan, Ahmed, had arrived together – they’d both been assigned to this place they had never heard of, the notice of which had initially disappointed them. How would they start a life in this tiny, backwater city, in such an unfamiliar culture and place?

They were brought to a hotel, where they were some of the first Afghans to arrive for the space contracted for their short-term housing. But 20-30 more people arrived each day in the subsequent week, until there were over 100 Afghans occupying hotel rooms.

The morning after his arrival, a volunteer arrived at his room with a hygiene kit prepared by the local Catholic Charities group, who were managing their resettlement. When he thanked them in English and asked a few questions, the volunteer exclaimed, “Thank God, we’ve found one of them who speaks English!”

From that moment on he was once again enlisted to help, which he did gladly. At first it was just translating. But then he realized that there were only a few volunteers available to help the 100+ people in need, so he just did what he knew needed to happen. He first created a WhatsApp group for all the resettled Afghans so they could communicate. Then, after asking the volunteers for use of a computer, he created a spreadsheet of all the different families’ names, details and needs, including the paperwork they carried or lacked, and their immigration statuses.

One day in that first week, Susan Montalvo-Gesser, a director at Catholic Charities, arrived at the hotel to give a presentation on immigration options for the Afghans. He translated for her, conversed with her afterwards, and then quickly became her right-hand man in the resettlement effort. He joined her at each consultation with an Afghan family.

But just weeks into their stay, in December 2021, a tornado passed through their region of Kentucky. The sirens went off at night, and the hotel staff directed Khaibar and other bewildered Afghans – who had never heard of a tornado – to shelter in the hallways for safety. In the morning, they learned the tornado had touched down 120 miles from them, and that the devastation was vast.

Susan had called Khaibar the next morning to say that all the immigration consultations with the Afghan families needed to be postponed. She had to travel to the area hit by the tornado to survey the damage. Khaibar asked if he could go with her.

“I am a disaster relief specialist, you see,” he told her. “I would love to help.”

“Sure” she replied. “Come along.”

Now, even amid his shock at the scale and type of devastation there, a kind he’d never seen, he had a sense for what to do. He and the team made a map of the area, and drove between counties, taking stock of which families needed what kind of help, and how soon. He went door to door with Susan and knew what questions to ask. This was the closest he’d come to feeling like the self he was back home in Afghanistan since the evacuation, and, tragic as the situation was, it felt good.

At the end of the day, as they were packing up to leave, Susan turned to him.

“Khaibar, would you ever like to work for Catholic Charities? I would like to officially hire you.”

She paused. “But I know you will need enough money to support your family, and we don’t pay very much. You can think about it.”

Khaibar smiled. “No, I don’t need to think about it. I’d love to work for you. We have a saying in Afghanistan that basically means, if you are generous, God will provide for you. I believe that.”

This is Part II of a multi-part story. The story will continue soon with Part III, detailing Khaibar's reunion with his family.

CLINIC wishes to thank Khaibar Shafaq for so generously sharing his story with us. Khaibar, we pray your story will change lives, and we thank you for your deep commitment to service.

Khaibar now serves as the director of migration and refugee services at Catholic Charities, Diocese of Owensboro, Kentucky, a CLINIC Affiliate organization.

We join many others in prayer for the thousands of Afghans under threat from the Taliban who still await resettlement and others who have arrived in the United States but lack legal status and live with great anxiety, often still separated from their families. For information on legal assistance for Afghans, please see this new resource from CLINIC.

This story was written by Kathleen Kollman Birch, with design by Ryan Saunders.