"I See My Own Family:" Fatima Hernandez and the UFW Foundation

Beginning the Journey.

Bakersfield, California.

"So, Fatima, can you tell us why you are interested in working at the United Farm Workers Foundation?”

Fatima sat across from the executive director of the UFW Foundation and the immigration legal services director. It was the long-awaited day of her interview to be an administrative assistant for the organization.

She hesitated. What should she tell them? That she and her husband needed the money? That she’d been out of work for a while, taking college classes, but that finances had gotten tight with the care of two young children?

“I…feel very dedicated and connected to the mission,” she stammered.

As she spoke the words she felt their truth, and in the span of a few moments her mind flashed back to several powerful memories from her childhood.

Fatima, age 6, feels her mother’s weight as it settles onto the edge of her bed. She stirs awake, pulling out of a dream. It is very early, around 4 a.m., and her mother is about to leave for work in the fields, capitalizing on hours of darkness before the heat of the summer sun. But she sits on the bed and places a hand gently on Fatima’s hip.

“Que Dios te cuide, te proteja,” her mother whispers with closed eyes.

"May God watch over you” – praying this because she, who will be in the fields until sundown, is not able to.

Fatima, age 7, picks green beans alongside her parents, noticing how her mother’s skillful, brown, worn hands move twice or three times the rate of hers as they drop beans into the bucket. It is after school, and she is tired and a little hungry. She watches her three older siblings pick beans beside their father, moving their hands nearly as skillfully, and her two younger siblings chase each other at the side of the field.

Fatima, age 8, sits with her siblings silently in the backseat of their van, anxiety washing over her like a wave. “Children, do not say a word,” their mother told them, white-faced, as the immigration agents approached the window. One of the agents, after conversing with her father in Spanish, turned to his colleague and said, in English, “Let’s let them go this time. The mother doesn’t drive, so if we take the father with us we’ll have to get someone to come tow the car.” The family drives away in silence, stunned with fear. It is many months before they get in the car again.

Fatima, age 9, stands in a long line in the hot sun, holding her mother’s hand. She is with her whole family, and they are one of what seems like hundreds of families standing in a line outside the Bakersfield, California, immigration office. Her mother’s grip on her hand is tight. Fatima knows they will wait in this line as long as necessary to get the medical exams and the process started to get their immigration status. It is 1986, and the immigration bill giving amnesty to millions of undocumented families has just been passed.

“I am never losing you again,” Fatima’s mother had said to her, referring to their experience of their separation at the border when Fatima was an infant, and the years of anxiety following it.

Fatima’s mind was pulled back to the office. She began to articulate some of these memories, and as she spoke, she felt how much she really did want this job.

Her tasks would be administrative, and the pay wasn’t great, but to work for an organization that assisted farm workers and their families with immigration concerns — that felt like something akin to a calling.

Gaining immigration status had changed her family’s life, and she wanted to contribute to an organization giving that opportunity to other people.

A few days later, she received a call from the director. She was hired. She would start this new chapter next week.

Don Carlos.

One year later.

Fatima stood in her office, organizing paperwork after another long day. She had just finished assisting Richard, the UFW Foundation legal services provider, with a series of back-to-back consultations with new clients seeking immigration benefits. She grabbed her keys and turned to leave.

"Fatima!” Richard beckoned to her from across the hall. He was standing with an elderly man, who was wearing a hat, and had sun-wrinkled, brown skin and kind eyes.

“This is Don Carlos,” Richard told her as she approached. “He is interested in applying for naturalization. Do you think you could help him?”

Fatima smiled warmly at Don Carlos, asked for one moment, then pulled Richard aside.

“Richard, you keep asking me for help with these cases, but you know I’m not a DOJ accredited rep like you. I don’t know how to do the paperwork. If I mess it up, he’ll be crushed.”

“Fatima, I know you — you are fully capable of becoming accredited, and I will help you with this case. It’s an easy one. He wants to become a U.S. citizen before he dies; it’s his lifelong dream. But I’m swamped. Please, help me out? I’ll review everything you do, carefully.”

Fatima frowned. Richard had been repeatedly encouraging her lately to start the process of becoming a Department of Justice accredited representative so she could take on some of the growing, heavy caseload for the organization. This was a special status that the DOJ granted so that non-attorneys could help represent clients in immigration processes. But she was nervous — she didn’t have a college degree, like Richard did, and she’d only been working there for a year. And immigration paperwork was serious stuff; one mistake and you could ruin someone’s chances of gaining legal status.

“Ok, I’ll try.”

Over the next weeks Fatima worked hard preparing Don Carlos’ application for citizenship. It turned out to be a delight getting to know him in the process. He was sweet, and his story reminded her of her dad’s, who had also come to the United States to make a better life for his children and ended up working decades of grueling hours in the fields picking food. Don Carlos was getting old, and he wanted to die a citizen of the country he’d lived in for most of his life.

Richard reviewed everything Fatima had worked on and sent off the application. He told Don Carlos to start preparing for his naturalization exam, which would happen orally because Don Carlos was illiterate. They helped him gather the appropriate study materials.

“Don’t you worry,” Don Carlos said. “I’ll be ready.”

On the day of his exam, Fatima whispered a prayer that all would go well. He was so eager, so earnest, and would be crushed if he failed.

The next afternoon Don Carlos walked into the UFW Foundation office, carrying a cake decorated with the words, “Happy Birthday.” He wore an enormous smile. Fatima was momentarily puzzled, and then she felt herself choking up when she realized he couldn’t read the words on the cake.

“I passed! I am going to be a U.S. citizen.” The staff members whooped and cheered.

Later, Richard turned to Fatima and said, “You did this for him. You did all the paperwork; all I did was review it and send it off. We need you as an accredited rep, Fatima. I know you can do it and you are going be great.”

She bit her lip. “Maybe, but it still feels like a stretch.”

Saying “Yes.”

June 2012.

On a June day in 2012, Fatima pulled up to the office entrance and cursed under her breath — the street was full of cars, and she was running late. Who were all of these people taking up the spaces?

She pulled over and got out of the car, and her jaw dropped. There was a line of 50 – maybe 100 – people standing outside the door of her office building.

A few seconds later Richard walked up next to her. He, too, stared at the line, speechless.

Just yesterday, on June 15, President Obama had announced a new program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). It meant that children whose parents brought them to the United States without documents before a certain date would receive protection from deportation and the ability to work and attend school legally in the United States.

Reading the announcement and watching the press session yesterday, Fatima had gotten goosebumps and her throat had choked up with tears. She knew what this program would mean to the immigrant and farm worker families she worked with — and she knew what it would have meant to her own parents, had they not been able to get citizenship through immigration amnesty in the late 80’s.

Now she was seeing the visible manifestation of what the program would mean to the community: parents, many of whom were missing work in the fields this morning — daily pay they relied on to sustain their families — waiting in line outside their office to apply for DACA for their children.

She and Richard went inside, opened the doors, and began doing intakes of the families waiting, taking names, numbers, and basic information for their cases.

They were there all day. It was an emotional, draining process.

Several mothers broke down in tears while Fatima asked them these basic questions.

“The application fee is so high, and I have multiple children without papers,” they said. “How can I decide which one of them to apply for first?”

Fatima did not know what to say, but her heart ached.

At the end of the day, she and Richard counted at least 100 clients in their notes whom they could potentially take on. And they knew there were more who would show up the next day.

“Fatima,” Richard said quietly. “I am going to need your help.”

This time, something shifted inside Fatima. She knew what her answer was going to be.

“Alright, Richard. I’ll apply for accreditation.”

In between helping Richard with client paperwork, over the next month Fatima got started with the application process. She signed up for the necessary trainings, many through CLINIC, and with close guidance of CLINIC staff.

She attended a 40-hour training in Pennsylvania. She continued her hands-on experience and learned from Richard. When she was ready, the director of the organization filled out her application paperwork.

Meanwhile, interest in immigration legal services from UFW Foundation was exploding — they continued to have lines out the door. Through the work of their directors, the tiny 2-person office began receiving grants to hire more people and expand their programming. It felt like the office was transforming overnight. Fatima began supervising the volunteers and new employees, but she longed for the day she could take on her own cases.

One day, many months later, an envelope addressed to her arrived in the mail. She opened it, and read, “This is to inform you that you have been approved for Department of Justice accreditation…”

“Richard, is this it? Just a little piece of paper?” Fatima found him buried in paperwork in his office.

His smile was ear to ear. “That’s it. Now you can get to work.” He was joking — sort of.

That night, Fatima drove to her parents’ house, where she found them in the kitchen.

“Mama, Papi, I have some good news. I received my accreditation, and now I can help our community with their applications for legal status.”

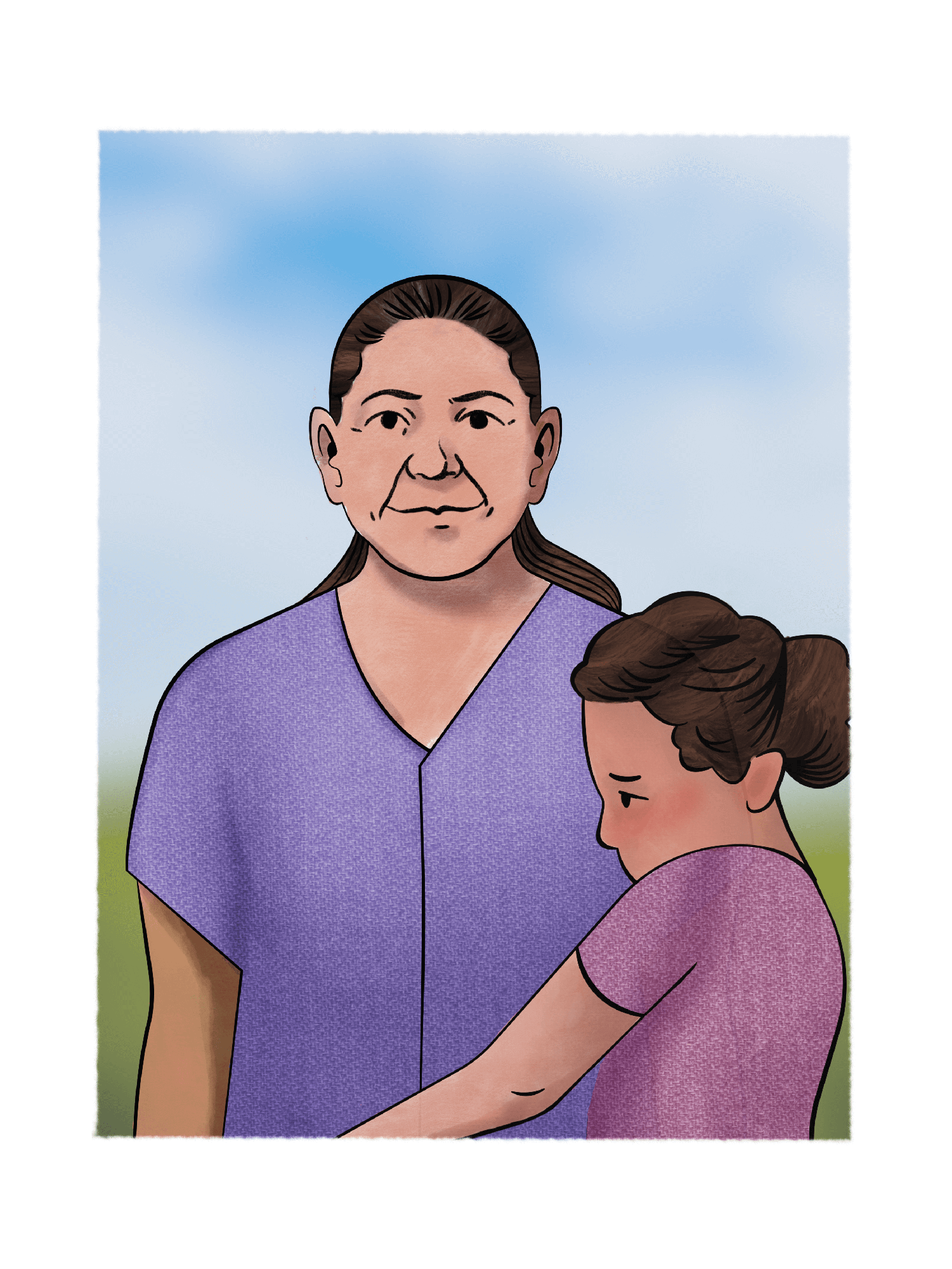

Her mother turned from the sink, grasped Fatima’s hand, and smiled widely. Her grip was tight and warm, despite the arthritis which disabled her after years of farmwork.

Her father embraced her. “I dreamed of good lives for my children when I came to this country, but I never could have imagined you would get to do work like this. I am so proud of you.”

Fatima tried to reply, but words failed her, and instead she gave a watery smile.

In the months that followed, Fatima dove into representing her own clients with passion and dedication. In each of the mothers who would cry in her office, or the fathers who twisted their dirt-stained fingers nervously as they talked through immigration options, she saw her own family.

The United Farm Workers Foundation was founded in the early 2000’s to support the farm worker community in Southern California through providing immigration legal services. It bears a close relationship to United Farm Workers, the union founded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, in the 1960’s.

The UFW Foundation, a CLINIC Affiliate, now employs over 135 people to provide legal and other social services to thousands of farm workers and immigrants. Following the announcement of DACA, the organization began growing exponentially — from a 7-person organization, to dozens of employees, and now over 100. The demand for immigration legal services for the farm worker community continues to grow, and many of the immigration legal services are provided by DOJ accredited representatives who come from immigrant families themselves.

Fatima Hernandez eventually began managing the immigration legal services at the Bakersfield office before she was further promoted to oversee the legal services programs at multiple locations across California. She now works as the Chief Community Advancement Officer, overseeing a range of services provided by UFW Foundation. She continues to train other DOJ accredited representatives and to encourage others to pursue this means of assisting their communities.

This story was written by Kathleen Kollman Birch through interviews with Fatima Hernandez. Illustrations were created by Ryan Saunders, CLINIC's Multimedia Designer.

CLINIC wants to express its sincere gratitude to Fatima for her willingness to share her story.

If you are interested in learning more about how to become a DOJ accredited representative, you can find more information on our website here.

To make a donation to support CLINIC's work expanding legal representation for immigrants, please click here.

CLINIC advocates for humane and just immigration policy. Its network of nonprofit immigration programs — over 450 organizations in 49 states and the District of Columbia — is the largest in the nation.