"In the Name of Compassion"

The Journey of Aden Batar

Somalia, March 1992

The rumble of the truck’s engine jolted Aden out of his reverie. Pulled out of his memories, which were more present to him than the hot sun on his face, he remembered where he was: in a truck, on the road from Mogadishu, Somalia, to the border of Kenya.

He had hardly eaten in days; his throat was dry with thirst; they had passed several bodies on the side of the road. But none of this mattered; only one thing mattered: getting to Nairobi, where he and his family could be safe.

Just yesterday they had buried Mohamed, his two-year-old son. An indirect casualty of the civil war in Somalia — a bloody power struggle which had broken out a little over a year prior — Mohamed had tripped on a pot of boiling water. Such an accident was not an uncommon occurrence for a toddler, but because of the war there had been no doctors available to treat the boy. He had died five days later as a result of his burns.

This was where Aden was, in his mind: with his wife, Asho, standing at the graveside, choked with tears, and then with her in the hours afterward when he had decided to leave Somalia.

Filled with dark anguish, with a consuming grief, he had known one thing: he had to leave, to find a safe way to get them out of there. There must be no more death of his loved ones.

No more.

This was the thought that echoed inside of him like a drumbeat, the driving force that had made his decision to leave clear.

Aden had left Asho and their other son, Jamal, only a few months old, with her family in the house of some relatives in Mogadishu, in one of the few neighborhoods still mostly safe from the violence. At least, he thought, if he died on the route, they would have family to look after them. Then he had gathered up what money they had left, bid his family an agonizing goodbye, and left for the trucks that he knew were headed for the Kenyan border.

He was risking his life in taking this land route, plagued by checkpoints, tribal conflict, militias and outbreaks of violence, but it was the only way. He could go ahead of them to find a safe route. He would gladly risk his death to prevent it for his family.

No more.

The truck rumbled on. Each mile they traveled was a mile closer to safety.

Nairobi, Kenya, May 1992

Aden and his cousin stood at the airport, squinting in the glaring afternoon sun as they gazed at the horizon. The little plane carrying Aden’s wife and son should be arriving any moment.

Aden’s heart was pounding, his breathing shallow. What if something had happened? What if the pilot hadn’t been able to locate his family at the airport in Mogadishu? What if soldiers had stopped them on the road? It was such a precarious plan, the details communicated to his wife via a shaky military radio current. Anything could go wrong.

He took a deep breath, slowing his accelerating train of thoughts. No, God had gotten them this far. He needed to trust.

A few days earlier, Aden and his cousin had tracked down the pilot of this plane. Each day, this pilot flew a plane of supplies over to Mogadishu — medicine, food, etc. Aden had learned from his relatives, who were long-time residents of Nairobi and well-connected, that each day the plane returned empty. There could be space for his family.

Aden had refused to have Asho and Jamal travel the perilous land route that he had taken. He had survived on that journey only as a matter of chance. And his family had no travel papers. They had to fly, and they had to do it informally. This was the perfect opportunity, if only Aden could convince the pilot.

Aden and his cousin had approached the pilot together, first offering money. The pilot had been cold, resistant — why should he take on the trouble of a woman and infant? Aden’s cousin, an influential person in Nairobi, had used various persuasive arguments.

In the end, Aden had shamelessly pleaded. “If you were in my shoes, what would you do to save your family?” Aden had said. “Do it in the name of compassion.” The pilot had begrudgingly agreed.

“There it is!” Aden’s cousin exclaimed. The little plane had appeared on the horizon, a tiny dot in the great cloudless sky. Some long minutes later, it descended to the ground.

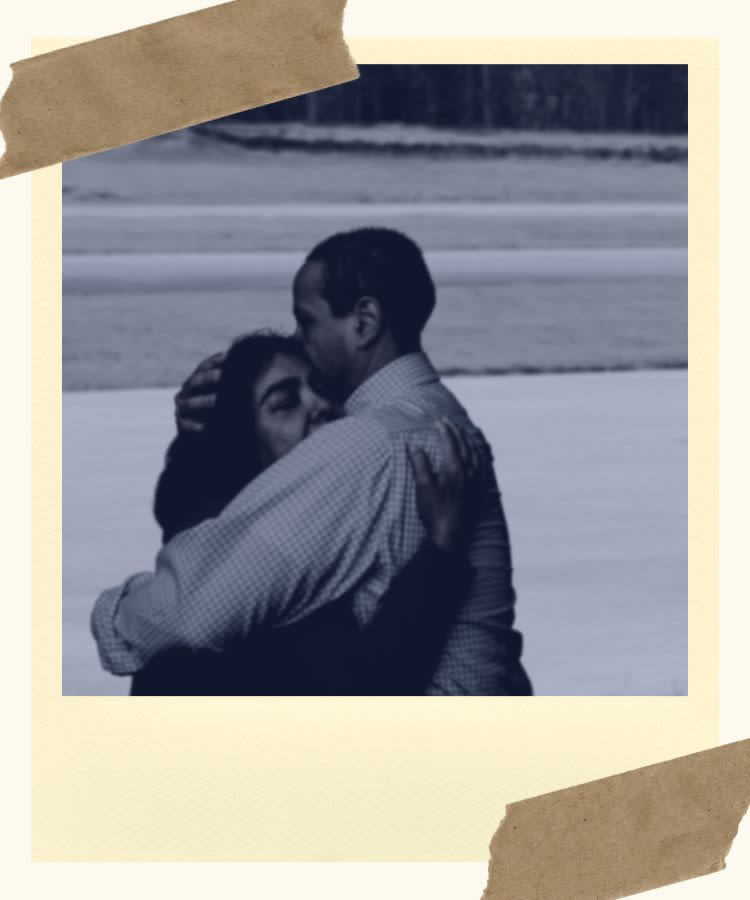

When Asho appeared in the doorway of the plane holding the baby, Aden’s tears flowed. His body trembled with joy and relief. He embraced the two of them and didn’t feel able to let go.

He caught the eye of the pilot, who stood a few yards away.

“Thank you, God bless you,” Aden said to him several times over, voice breaking. “You have saved my family.”

The pilot, previously gruff and distant, had tears in his eyes as well.

Aden took Asho and Jamal to the house of the relatives with whom he’d been staying. Seeing them in the little bedroom he’d been occupying alone for months felt surreal. Here he had prayed for them and longed for them. As they went to sleep that night, all three in one small bed, he held them close and ached with happiness.

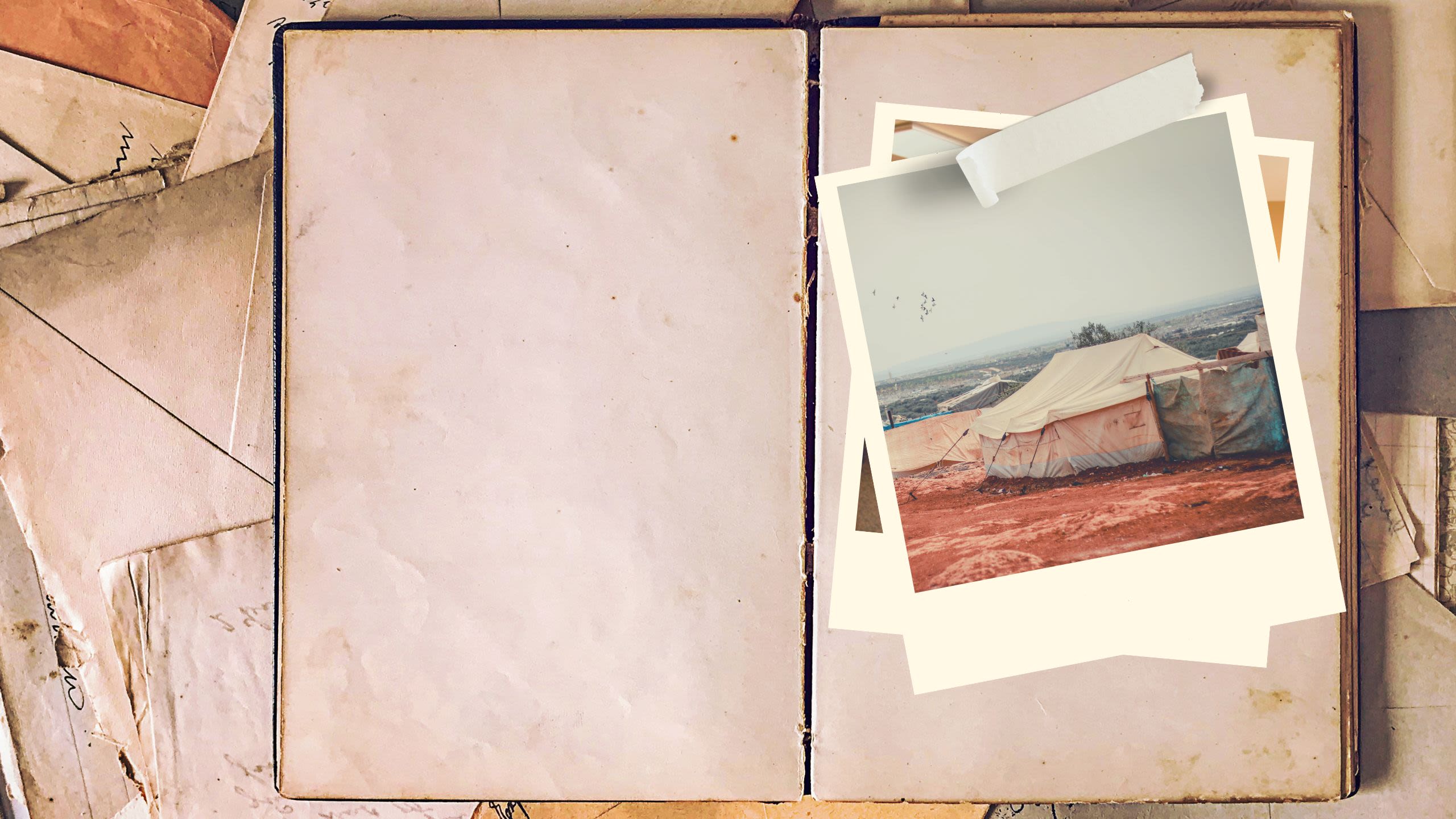

Mombasa Refugee Camp, Kenya, 1994

Aden and his family filed into the resettlement office, crowding the small space. He had with him Asho; their two sons, one a newborn in his mother’s arms; and Asho’s parents, whom they’d managed to bring over from Mogadishu as well. The immigration officer welcomed them with a smile and then shut the door behind them.

This immigration office was a familiar space for Aden. During the two years they had been staying in Nairobi with his relatives, Aden had been volunteering periodically at this refugee camp in Mombasa, a day's ride away.

In between the informal paid jobs he had gotten in Nairobi, he came to the camp for days at a time to help translate for the Somali refugees and the English-speaking staff. Among the many Somali refugees here in Kenya, Aden knew he was blessed; he had received a good education back in Somalia, a university degree and then a law degree. He felt a sense of duty to help other Somalis who had been less fortunate.

“Thank you all for coming today,” said the immigration officer, who had conducted a final interview with the family several days before. He approached Aden and handed him an envelope.

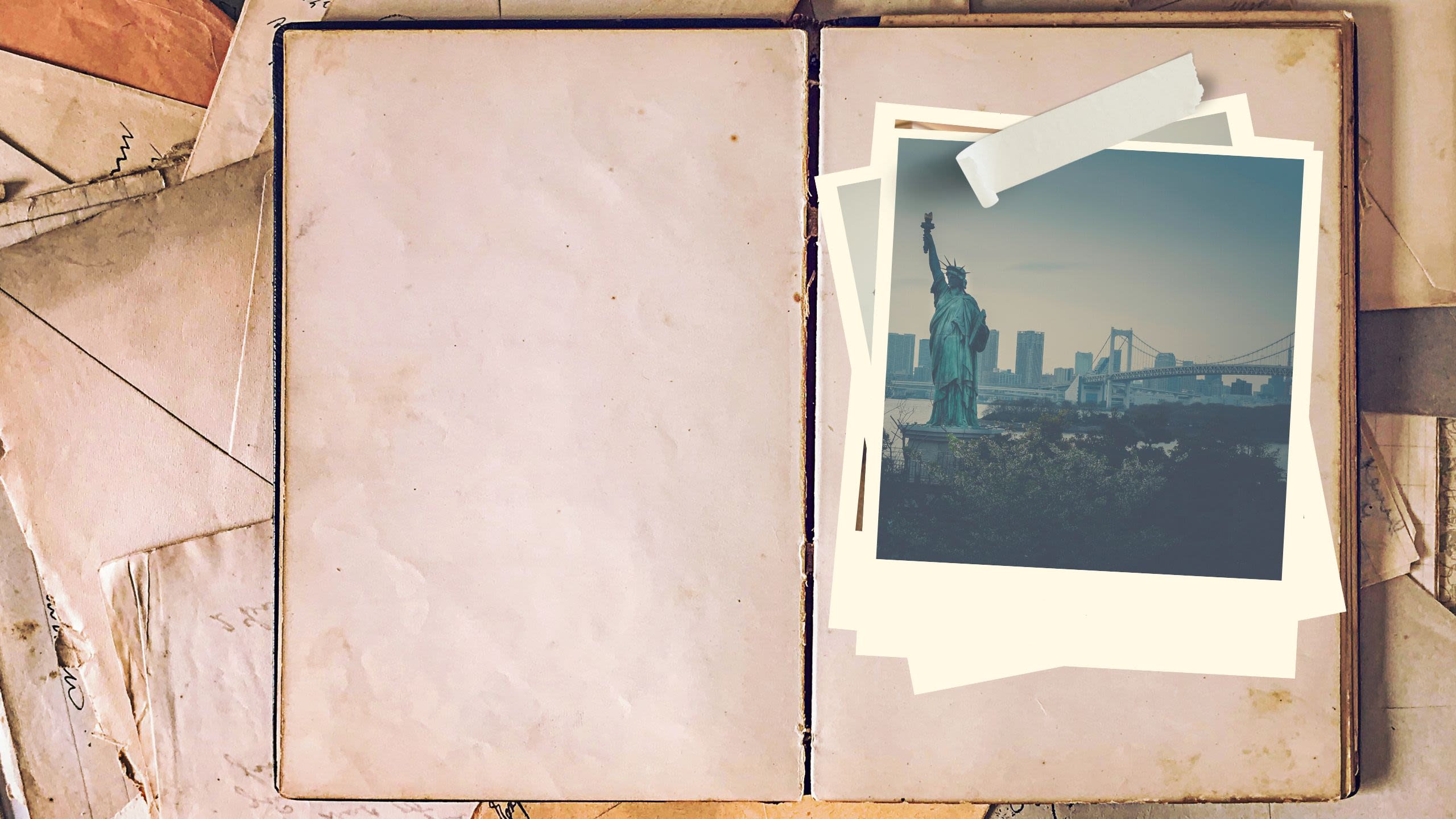

“Aden, my friend, I won’t make you all wait to open this to know the decision. Welcome to America.”

“Praise God!” His family erupted in jubilation, raising their arms and crying out. They embraced one another and repeated, “America! We are going to America!”

Aden himself was speechless. Was this truly happening? Could they all really be safe together in the United States? He was happy, overjoyed even, but cautiously so. It wouldn’t feel real until they were there.

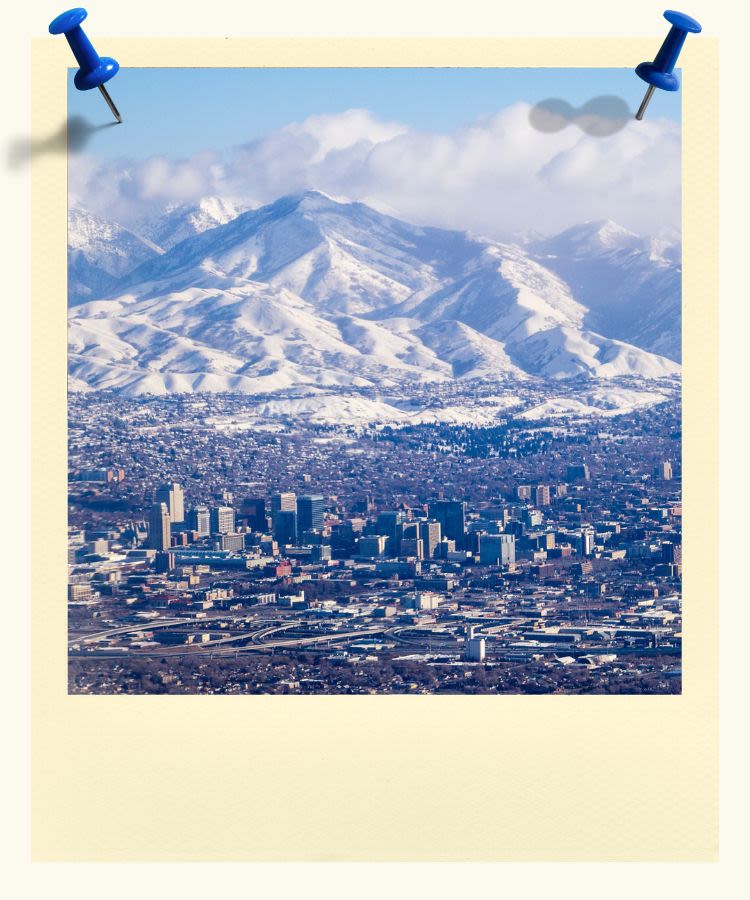

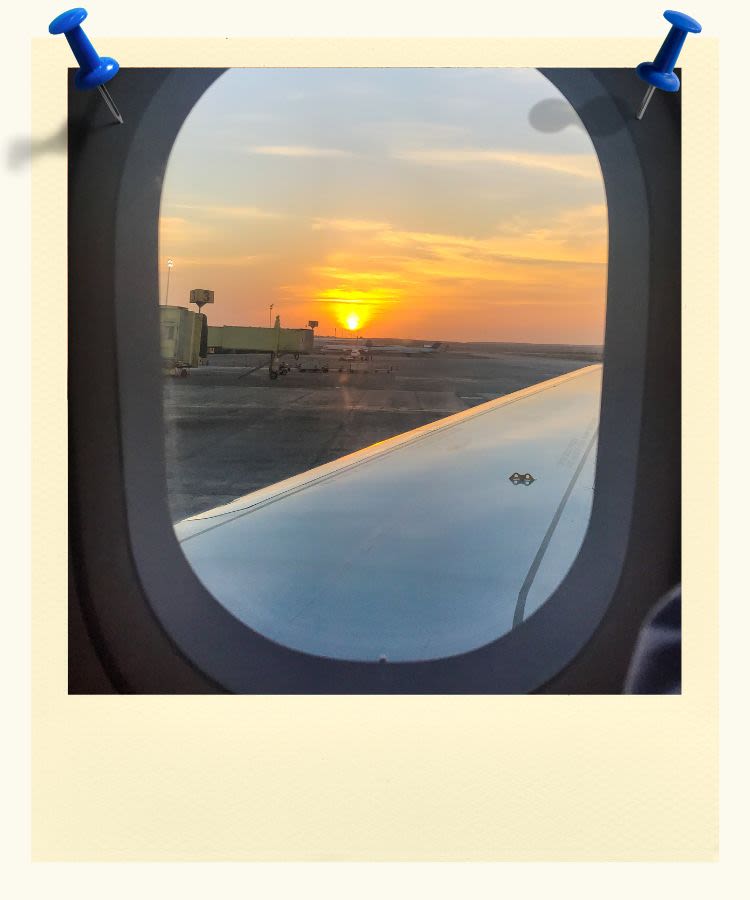

Salt Lake City, Utah, May 1994

As their plane touched down at Salt Lake City International Airport, Aden looked out the window at the mountain peaks in the distance. Their glistening, snow-capped peaks were beautiful. He had never seen snow before.

He closed his eyes and breathed. They were here, finally.

It had taken them over 20 hours of travel to reach this final destination — first, a plane ride to Germany, then to New York, overnight at a motel, and then to Salt Lake City, all with two squirming little boys on their laps. Aden knew he was exhausted, but adrenaline — and a sense of duty — kept him going.

He was going to make sure his family was okay here, in this new country. Find a job, build a life, make his family happy. It was a long, difficult road ahead, but at least here, they were safe.

“Aden! Over here!” His brother-in-law, Issa, called out to him as they exited the airport terminal. Issa had arrived several years prior and had been able to sponsor Aden, his wife and sons, and Aden’s in-laws to join him in Salt Lake City. Issa embraced his sister, then Aden and the rest of the family.

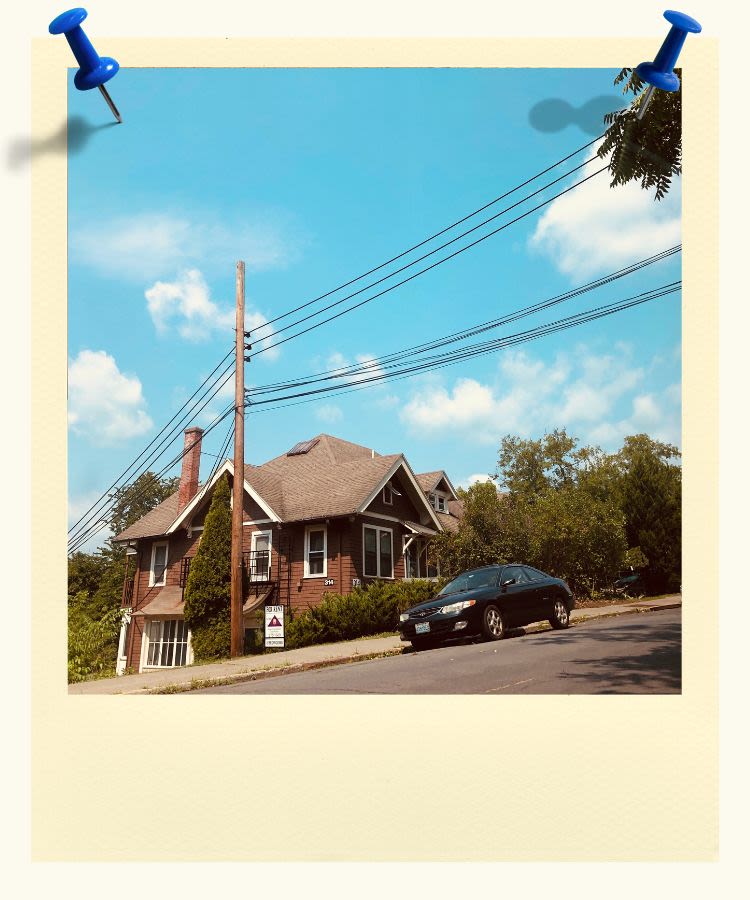

Issa was standing with a group of volunteers from the local resettlement agency. Aden’s family was the first group of Somali refugees that were being settled by Catholic Community Services, the local Catholic resettlement agency. The volunteers wore warm smiles. They beckoned them into waiting vehicles, which would take them to their new home.

As they pulled up to the house, Aden was surprised to see its size. He hadn’t realized his brother-in-law could afford such a large home. “This is where we are to live?” he murmured, and Issa nodded with a smile.

They entered the home. It was spacious, five bedrooms, with comfortable furniture. There were groceries piled on the table, clothes in the closets, dishes in the cabinets, and a pile of toys, which his two little sons immediately approached.

“Issa this is your home?” Aden turned to him. “Well done, it’s great. Just let me know where we can place our things.”

“No, my brother,” Issa replied.

“This is your home. I rented it, and the resettlement agency furnished it and got it ready. It’s for you all.”

Aden blinked and Asho gasped. Theirs? Aden’s mind flashed back to the one bedroom the four of them had shared in Kenya, with its single mattress. And now here, a home, all ready for them. He swelled with emotion at the kindness of strangers.

He heard a noise from the other room. His toddler, Jamal, had found the living room and was jumping on the couch and squealing. Aden laughed and felt relief run through him like a current. He knew they would have to start over here, build a life from scratch, but this — this was one huge step forward; everything they needed at first was here ready for them.

Here, after so long, they could be at home.

Salt Lake City, Utah, 1996

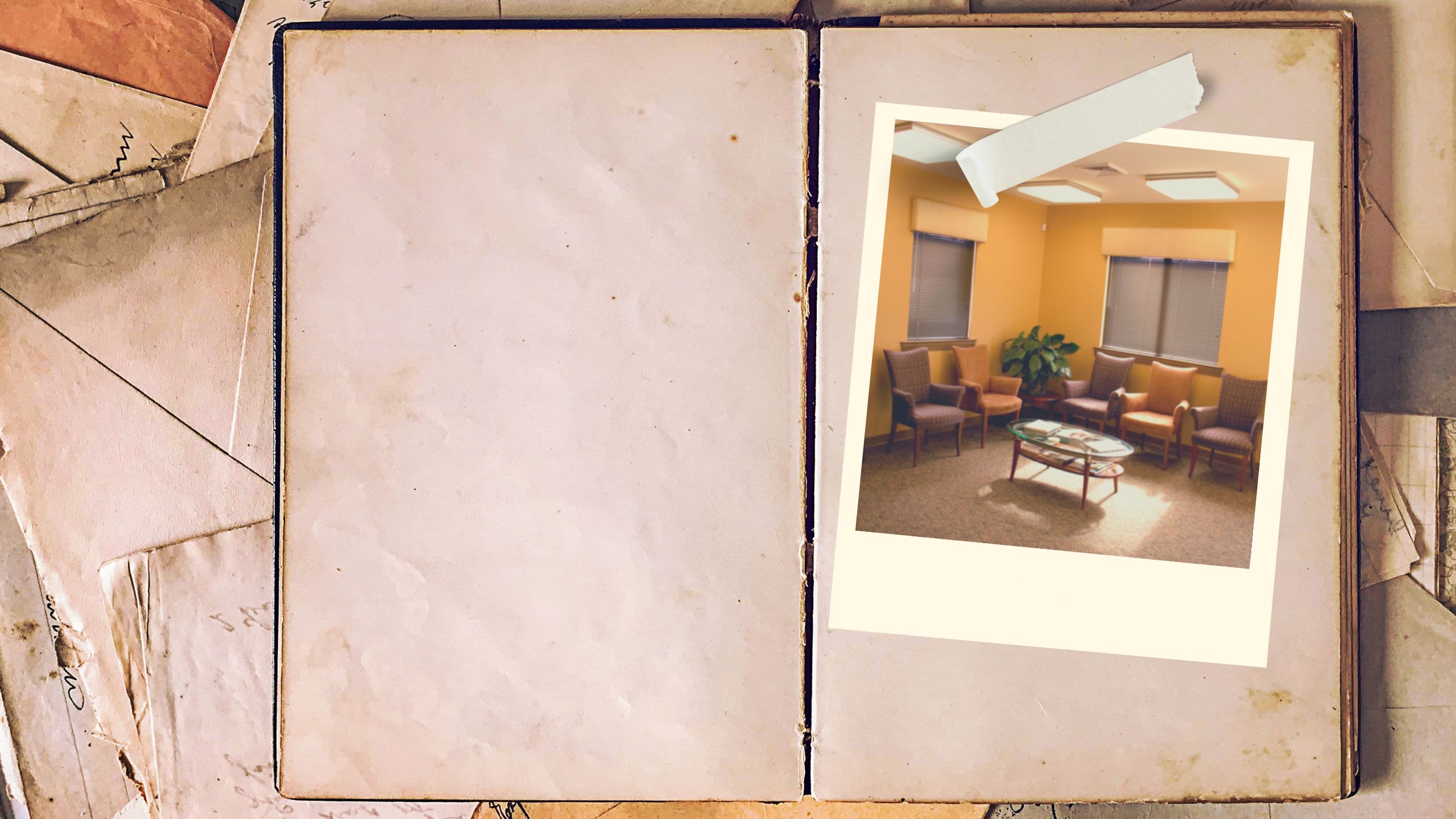

Aden swung open the door to Catholic Community Services and walked inside. He warmly greeted the employees there, with whom he’d become familiar over the months since his family had arrived. The agency had worked closely with Aden to help him find work and get settled there in Utah.

He found the office of the program director, Lina, and knocked.

She opened the door and smiled. “Aden, come in! How can I help you?”

“Good morning, Lina. I am wondering if you know of any job openings. I am grateful for my work on the production line that your office helped me find, but I’m looking for something else.” Aden didn’t need to explain further. She knew the job he was doing was exhausting, with long hours, and that his English skills and his legal training back in Somalia equipped him for other work.

“Aden, you couldn’t have come at a better time,” Lina said. “We need a new case manager. We have a family of eight Somalis arriving tonight and we have no one to greet them or translate. Would you like the job?”

Aden hesitated for a moment. The resettlement office was almost an hour away from his family’s home. But this was a rewarding job, and higher pay. “I need to speak with my wife, but think I would like to take it. Thank you so much.”

“Great, can you start today?”

Hours later, Aden was greeting the Somali family at the airport, standing exactly where the volunteers had greeted him months before. He could see the relief in the family’s eyes when they saw him, and he started speaking to them in the Somali language.

Aden didn’t finish work until midnight that night. As he said his nightly prayers, he thanked God again and again for the blessing of this new job. He went to sleep awash in gratitude.

Salt Lake City, Utah, 2009

There was a knock on the door of Aden’s office. “Come in!”

One of the office’s caseworkers entered, followed by a tall, middle-aged Ethiopian man. “Mr. Batar, this is Isayas Tekeste.* He requested specifically to speak with you.”

Aden thanked the staff member, then gestured for Isayas to come in and sit down. The two men sat across from each other.

“Welcome to Catholic Community Services. My name is Aden Batar and I serve as program director of immigration and refugee services. What is it I can help you with today?”

“Sir, I need your help reuniting with my family. I haven’t seen them in 10 years.”

The man’s story poured out: how he’d fled civil war in Ethiopia and in the process gotten separated from his wife and daughter. How he’d been resettled to the U.S. and had been trying to bring them over, unsuccessfully. How it had now been 10 years since he had seen his daughter, who had been a child at the time and would now be nearly grown. His wife had since died.

“I don’t know that I would even recognize my daughter now,” Isayas said, his voice dropping low.

In the years since becoming a caseworker, then working as program manager, and now program director, Aden had heard many stories of refugee clients. But there was something about this man’s story that moved him; maybe it was the way the man spoke of his daughter, with tenderness and grief for the lost years, or perhaps the desperation and hungry longing in his eyes.

It stirred in Aden fresh memories of the pain of his own journey: the grief, fear, loss, and anticipation. The single-minded goal of seeing his family, and the total relief at the reunion. He was surprised to find his eyes smarting with tears.

He cleared his throat. “Sir, I promise you I will do everything in my power to help you,” Aden said to Isayas.

Over the next weeks and months, Aden filled out Isayas’s paperwork to file for his daughter to join him in the United States — personally, by hand. As a busy program director, he didn’t take on many direct clients anymore, but he felt this one was something he needed to do.

Isayas would come in weekly to check on the process, which took weeks, then months, then almost two years.

One day, Aden finally got word that Isayas’s daughter had been scheduled for a flight to the U.S. He called Isayas to tell him. Hours later, Isayas was at the office, bringing cookies for the whole staff. Everyone was drawn into his joy.

Aden accompanied Isayas to the airport on the day his daughter was to arrive in the U.S. Isayas was happy, but full of nervous energy. “I just don’t think she’ll recognize me. Will I recognize her? She was a little girl when I left.”

Isayas scanned the crowd of people streaming out of the terminal. When he finally caught sight of his daughter, his eyes widened, softened, then glistened with tears. His daughter’s eyes searched the people waiting, too. She caught sight of Isayas, and a smile spread across her face.

They embraced. Aden, watching it all, was transported back to the airport in Nairobi, to the sensation of holding his wife and son in his arms after their separation.

Isayas looked over his shoulder at Aden.

“Thank you, God bless you. You have saved my family.”

Aden Batar (left, front) with his family.

Aden Batar (left, front) with his family.

This story was written by Kathleen Kollman Birch, CLINIC staff member, through interviews with Aden Batar. CLINIC wishes to express its deep gratitude to Aden for sharing his story.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.

CLINIC advocates for humane and just immigration policy. Its network of nonprofit immigration programs — over 450 organizations in 49 states and the District of Columbia — is the largest in the nation.