Rooted in Service:

Ricardo Morales Bermúdez and the Leadership Academy for Immigrants in Southern Arizona

The Immigrant Experience. Tucson, Arizona, 2015

On a sweltering, late afternoon, Ricardo Morales pulled into his in-laws’ driveway. Before going inside, he took out his phone and opened his email to check for messages from potential employers. Wiping the sweat from his brow, he clicked on an unread email from a nearby clothing department store.

“Dear Mr. Morales, we thank you for your application, but we are unable to offer you employment at this time…”

Ricardo’s stomach plunged. Frustration, shame, and embarrassment washed over him. With his excellent language skills, job history, and college education, he could not even get a temporary job at a retail store?

Taking some deep breaths, he lingered in the hot car for a moment to compose himself before going inside to greet his wife and her parents.

For the first time since immigrating to the United States, an unbidden thought filled his mind.

“What have I done?”

He and his wife had moved here to Tucson from his native state of Guadalajara, Mexico, just a handful of weeks before. He had been happy to come, generally — glad to support his wife, a U.S. citizen, in reuniting with her parents and in taking a new job here in Tucson. She had been lonely and homesick in Mexico, and he was usually open to new things. But the first weeks after immigrating to the United States had been harder than he could have imagined.

Every day for the past few weeks, Ricardo had left the house to search for work, submitting countless resumes and trying to make connections. They needed the money; they were trying to move out of his in-law’s house. But at nearly every place he’d stopped by — from professional settings to retail stores — his characteristic wide smile and enthusiasm was met with blank, cold looks, no signs of recognition or interest in his background or capabilities.

One clerk had brusquely informed him that he needed to remove the photo on his resume and resubmit it. He had blushed with embarrassment as she handed it back. It was common in Mexico to put a photo on a resume; clearly not in the United States.

This disdain and lack of interest he was facing stung, touching him in a deeper place than he’d anticipated. He went home at night deeply discouraged, though he hid it from his wife’s family.

At certain moments he would be flooded with memories of life back home. The beautiful, tropical climate; the way he was greeted warmly everywhere he went; the weeknight dinners with his parents. He recalled how he and his family had been constantly involved in community events in organizations — go-getters and volunteers, the lot of them. His father’s campaign for town mayor several years prior had epitomized this family characteristic.

Every week he was involved in events at his parish or with local organizations; on the weekends, he was at barbecues at his grandparent’s house, or visiting various relatives and friends.

In his former job at the U.S. consulate in Guadalajara, which he had loved, his role had been to welcome U.S. immigrants to Mexico, using his broad social connections to help them through the difficult experience of being a stranger in a foreign place.

In Guadalajara, he’d had what his clients at work lacked: a web of connections and relationships that made him feel stable, grounded, and proud of who he was. Through his work, he was able to give to others from the abundance he had, giving his days meaning and orientation.

Now, here, that web had disintegrated. He felt suspended in the open, untethered.

Who was he in this totally new place, where he knew almost no one? Where were the people who could help him navigate this foreign experience?

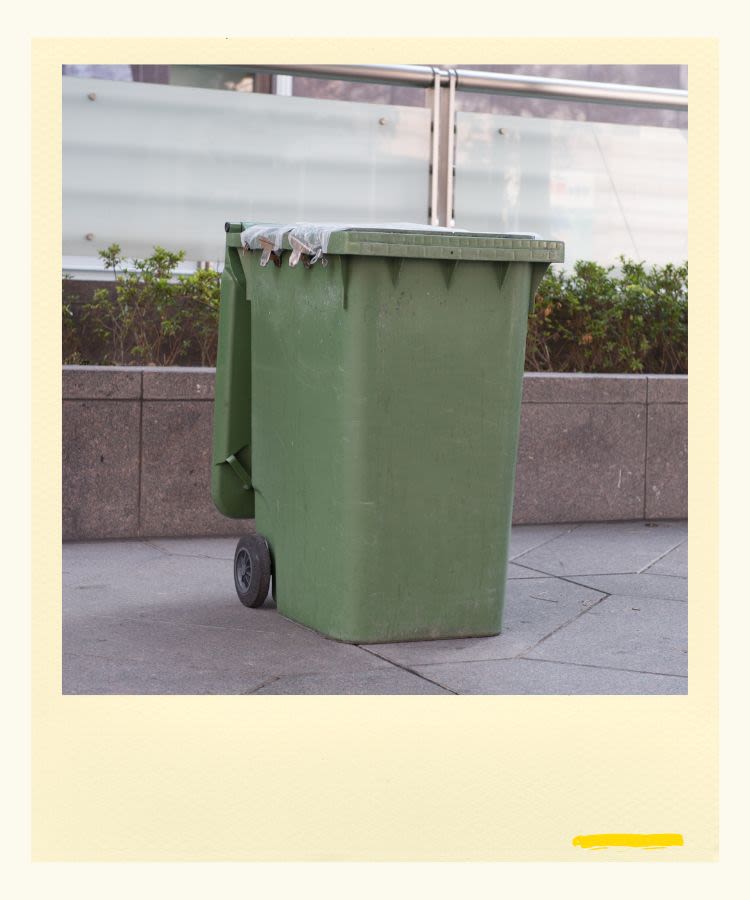

He got out of the car, and as he moved toward the house he noticed that the overflowing green bin, which sat on the curb, had not been picked up. Hadn’t he put it out that very morning for trash day? He cursed under his breath — he had put out the wrong bin. Here it was the opposite as in Mexico: the green bin was for recycling, the blue for trash.

It was a small mistake, but it bothered him — even the simplest things in this country were different, and therefore difficult.

The Grant. Six years later. August 2021.

“Ricardo, I think you should take over this National Immigrant Empowerment Project grant.” Ricardo’s supervisor handed him a folder of papers. “Take a look and see what you think.”

As his boss left the office, Ricardo opened the folder and leafed through the pages. He felt a flutter of excitement in his chest. This was the first week of this new job at Chicanos Por La Causa, or CPLC, and it was exactly the kind of work he’d dreamed of doing.

A few months after moving to Tucson five years ago, Ricardo had finally found work after volunteering with the Tucson chamber of commerce for a while, building connections and experience in the community until the office had found the money to hire him.

After that job he’d worked for several years at the Mexican Consulate in Tucson, in various roles with the cultural and economic concerns, public affairs, and legal affairs departments.

In these roles he’d gotten exposed to what felt like all facets of the immigrant experience. For a time he’d worked on a general help hotline for Mexican immigrants to the United States, where he’d received requests that ran the gamut — from Mexican entrepreneurs looking for business advice; to new immigrants looking for jobs in construction or landscaping; to Mexican migrants stranded in the desert between Mexico and the United States, desperately calling the Consulate hotline for aid.

In summer 2018, while working in the legal affairs department at the Consulate, he’d helped Mexican parents separated from their children at the border become reunited. This was one of the most meaningful experiences of his life — and it had given him a heightened passion for making sure immigrants’ rights and dignity were respected.

He’d loved those jobs, but they had made him long to be working even more closely and directly to address the needs of vulnerable immigrants in the Tucson area. He’d been on the lookout for jobs at the grassroots level, in community organizing and immigrant engagement.

Now, at Chicanos Por La Causa, he would be doing just that.

CPLC was an organization founded in the late 60’s by a grassroots movement of Mexican immigrants seeking to address the lack of resources available to low-income Latino communities, originally in Phoenix and now around the Southwest. It was widely known and respected for its work, and, in his previous jobs, Ricardo had admired the organization for addressing the gaps he saw in outreach to Latino immigrants.

In those first few years in Tucson, through his work and personal experiences, he had seen his own immigrant experience magnified in the lives of so many other Latino immigrants he came in contact with, who came to this country with far fewer resources than he had. He knew immigrants who struggled to find work because of language barriers and lack of education. Others who couldn’t navigate the health system because they didn’t understand the U.S. concept of preventive care or insurance. Other impoverished families who would have qualified for numerous social support programs but didn’t have the capacity to navigate bureaucracy.

He saw it over and over again: that a lack of network and involvement in community prevented so many new immigrants from feeling at home here, knowing their own rights and dignity, accessing help and resources, and giving back to their communities.

The booklet he now held in his hands described a grant that CLPC had gotten from an organization called CLINIC to create a project to promote immigrant empowerment, community integration, and leadership through grassroots organizing. It was called the National Immigrant Empowerment Project.

Ricardo immediately recognized the need for such a project in Tucson. The staff at CPLC Tucson had just been discussing the fact that over 40% of the city population was Latino, but that percentage was not nearly reflected in city or local community leadership.

The needs of Latino communities and the challenges they faced — especially recent immigrants — did not often rise to the ears of the city’s leaders. But where to begin to address that problem?

Ricardo considered what he would have wanted as a new immigrant two years ago: a place to gather with other immigrants and discuss common concerns and frustrations; a structured time to learn about how the city worked, how to access resources and make connections. A place to discuss how to celebrate and honor — and not hide or diminish — cultural identity and Spanish language. A group of people who knew the city who could make him feel welcome.

He began to envision it: a program, or class, in community leadership for immigrants. The students would learn from the instructors and one another through sharing their experiences. They'd gain the tools to go out and start their own initiatives in their neighborhoods and communities.

As the vision crystallized in his mind, he began to realize what it would take to create this. First of all, input from others. How would he shape the curriculum? How would he ensure it really addressed the diverse and far-reaching needs of immigrant communities, especially those whose experiences were different from his own? He’d need to speak to other immigrants. He’d need buy-in from other community leaders. They’d need a place to gather.

Would it work? Could he pull this off?

Full of nervous excitement, Ricardo got out his laptop and began sending a flurry of emails.

The First Day of Class. January 2021.

“Welcome, all, to the first session of the Leadership Academy for Immigrants in Southern Arizona. I am so glad you all are here.”

Ricardo stood at the front of the conference room looking out at the 13 students of the first cohort of the Leadership Academy.

He hoped the mask he was wearing hid the slightly nervous edge in his smile and voice. Today — this first day of the immigrant leadership program, the first of its kind in Southern Arizona — was the culmination of many months of preparation.

With the help of contacts at the Guatemalan and Mexican consulates, he had done extensive interviews with immigrants in the community to craft the content and gauge needs. He’d written the program content and created learning objectives. Finally, he’d solicited applicants for the program, which had proved a very difficult process, as it required convincing people to sign up for an eleven-session, in-person program that had never happened before, promising them it would be worth their time.

And he had done all of this in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 13 registered students were diverse in their backgrounds — some were recent immigrants, some had immigrated years ago. They were of various nationalities, mostly Mexican and Guatemalan. Some were highly educated, some not. They ranged in ages and backgrounds, from young women who worked in the home to middle-aged individuals with professional experience. All spoke Spanish, as the program was to be held entirely in Spanish. The class was meeting in the evenings 6-9 p.m., at the students’ request, so that even those who were single parents or who worked two or three jobs could attend.

Now, Ricardo went on to give an overview of the program to the new students, explaining that over eleven, three-hour sessions they would cover many topics related to community leadership and immigrant integration, including city government and its functions, civic engagement, arts and culture, healthcare and economic issues, and border issues.

There would be speakers from the community at each class — local leaders — and the class would make regular field trips to visit local institutions and make connections. The program would culminate with a class project, a community engagement initiative which they had to plan and carry out together.

After he finished speaking, he looked around, and saw some eyes looking at him with interest and eagerness, while others looked a bit overwhelmed, maybe even skeptical.

He cleared his throat. “But to start, we’re going to start with some get-to-know you activities, so you can meet your classmates.”

First, he had them play a bingo game, where they walked around and asked each other basic questions, filling in squares on their sheet if their conversation partner “liked to cook,” or “owned a dog,” etc. This broke the ice and got every one to at least interact with each other person in the class.

Then, he gave each of the members of the class some paper and writing materials. He instructed them to take five or ten minutes to sketch out, visually, the story of their life and immigration journey. They would then have the opportunity to share with the class if they wished.

After ten minutes of silence, he asked for any volunteers to share.

A woman, small in stature, with hair tightly caught up in a bun, raised her hand. Ricardo gestured at her to go ahead.

“My name is Margarita,” she said. “I am from Guatemala, but I am part of the Maya K'iche' people.”

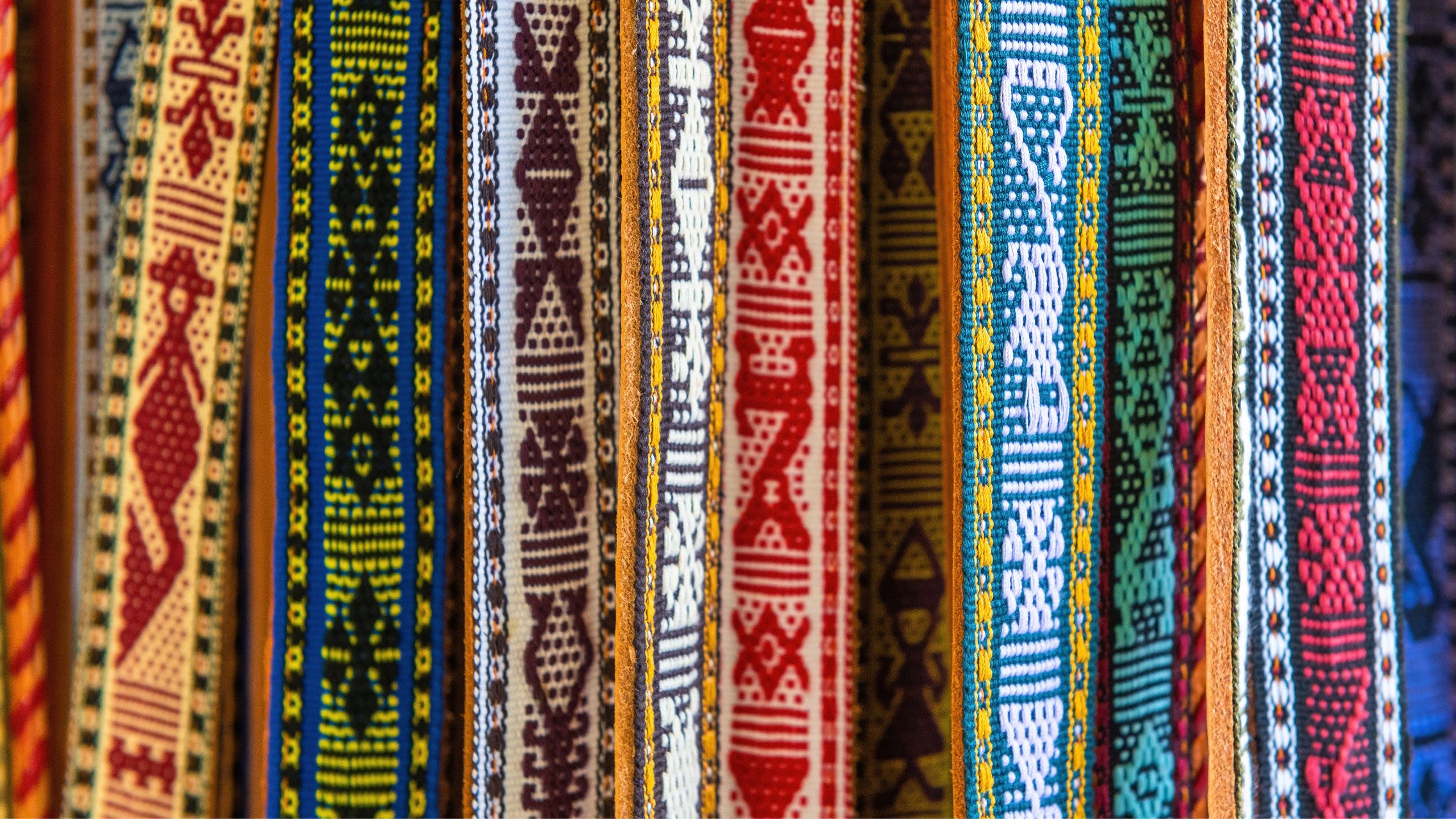

Margarita explained that she had grown up in a small mountain village in Guatemala, speaking only the Maya K’iche' language. When she moved to Guatemala City as an adult to find work, she had been bullied and abused for her poor Spanish and for wearing Mayan traditional clothing. Eventually, she learned Spanish, became a teacher, and got involved in the community. She stopped wearing her traditional clothes, but in her spare time she began advocating for human and Indigenous rights in Guatemala.

But upon immigrating to the United States, she once again felt very aware of her vulnerability and how different she was from the general population, including other Latin Americans. She mostly worked and stayed in the home, too anxious to engage in society. But she had seen the leadership program advertised and something in her had known she had to come.

Ricardo’s heart swelled as he heard Margarita’s story. He could see other participants listening intently, some even nodding in recognition of the troubles she faced. There was another woman in the program, Monica, whom he knew was also Indigenous. He felt he could see her body language relax as she listened to Margarita’s story.

When she finished, there were a few seconds of quiet as the room absorbed what Margarita had shared. Then another person’s hand went up.

One by one, their stories trickled out. As the activity progressed Ricardo felt the energy in the room shift — now, there was a sense of recognition, of solidarity, of their being some sort of a united group. There was a feeling of potential in their shared experiences and concerns. What would they do with it?

The Class Project. March 2021.

It was late — 15 minutes till the end of class — and everyone was ready to go home. But the students were mired in a debate, and there wasn’t an end in sight.

The program was, in general, going swimmingly — they’d made it through most of the program content, and the students were thriving. They were nearing graduation from the program, with only a handful of sessions left. They were all eager to go out and use the skills they’d acquired to address concerns in their own communities.

What stood in their way was the final requirement of the program: the culminating class project, which had to be a community engagement project carried out by the whole group. Despite much discussion, the class had not narrowed in on a project.

They faced several barriers, one major one being the difficulty of carrying anything out during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was surging again. The other barrier was their diverse set of interests — a decent portion of the class wanted to carry out some sort of sustainability campaign, but others were more interested in something more concrete, like a resource fair for the Hispanic community.

All Ricardo knew was that they needed to decide something quickly, and then make it happen. Part of growing in leadership was making joint decisions and navigating disagreement. Part of it was also knowing how to get things done on a tight timeline.

“Alright, anyone have another idea to suggest before we wrap up?” Ricardo said.

After a moment one student, Isabel, raised her hand.

“Well…there’s this park, in a neighborhood I know of,” she said. “We could refurbish it. It needs a lot of help.”

Ricardo cocked his head. The other students looked confused. What was so special about this park?

Isabel went on to explain. The park was in a Hispanic, underprivileged neighborhood. It was not owned by the city, but by the local neighborhood, and there was no money or time available for its maintenance. Over the years it had become dilapidated and overgrown. If they could figure out a way to clean up the park, it could become, once again, a meeting spot for that neighborhood, and a place the community could gather and be proud of.

The students seemed to be nodding, expressing their comprehension. Ricardo, too, understood: this park in need of restoration was not just a park. It was a symbol of lack of investment in the neighborhood and lack of resources.

The more he considered it, the more it made sense. It was a concrete, realistic project, and one that touched on the sustainability interests of the group. It would require the students to collaborate on practical implementation, to get in touch with the leaders of that neighborhood, to ask community members about the needs of the park, and then acquire the tools to do it: the paint, lawn maintenance, or any construction material needed.

This project — simple, but meaningful — could be perfect.

Fifteen minutes later, they had finally agreed. The students trickled out, abuzz with excitement, energy and hope.

Restoration and Integration: April 2021

“Excuse me, but who are you all? Why have you come to fix our park?”

Squinting in the sun, Ricardo watched from afar as a man and woman from the neighborhood approached a group of his students, who were knelt down while working on refurbishing a park bench.

The students stopped what they were doing, introduced themselves to the couple, and began to explain about the Leadership Academy and the park restoration project. He watched the woman from the neighborhood begin to nod and smile in gratitude. She gestured to her home, which overlooked the park.

It was a warm, lovely spring day in Tucson, and the class was about halfway through their project of renovating the park. The park was looking almost transformed already — the overgrown vines and branches were cut back, the trash picked up, the grass was cut, the rotting wooden structures replaced and in the process of being painted.

The students had arrived that morning full of energy and enthusiasm, despite the difficult work ahead of them. Many of them had brought their families to help, explaining to Ricardo that they wanted their families to see what they’d learned, to grow along with them in community engagement. The students greeted each other’s families warmly.

As they had begun work that morning, Ricardo thought his students looked different, happier — then he realized that it was the first time he had seen their smiles, their full faces without masks.

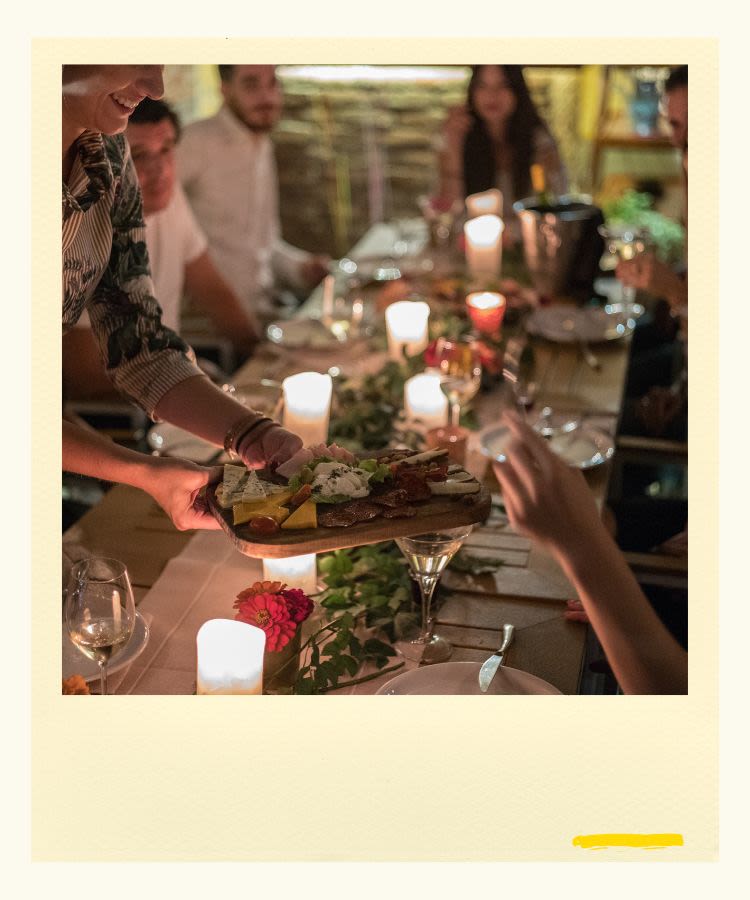

Now, Ricardo’s students returned to their work on the bench, and the woman and her husband walked away. But about thirty minutes later, the couple was back, bringing with them a group of their neighbors. They were holding lemonade and Salvadoran pupusas, which they passed out among the students. Ricardo’s students paused their work around the park and gathered to eat, drink, and chat with this group of people from the neighborhood.

As he joined one of the conversations, he heard his students speaking assuredly about their project and the program goals. Ricardo’s smile widened.

They were taking initiative; they were confident in themselves; they were making connections across the Hispanic community, becoming leaders.

A few weeks later, Ricardo held a graduation ceremony for this first cohort of students. At the graduation, Margarita came to the podium to speak.

“This program has changed my life here in the United States,” Margarita said. “I plan to use what I have learned here to start a cultural heritage group for Latin American Indigenous people in Tucson. I am proud of who I am, where I come from, and what I can give to this community.”

Ricardo felt himself getting choked up. His smile quivered with emotion as he noticed that Margarita was wearing her traditional Indigenous clothing.

She — like many of the other students — was so beautifully realizing one of the goals of immigrant integration: the ability to recognize oneself in this new place, to carry over the deepest pieces of who one was in the country of origin and embody them boldly and joyfully here as well.

In helping the students achieve this integration, Ricardo felt in his bones that he, as an immigrant, was now living that reality himself as well.

Relief, pride, and hope washed over him. Despite COVID, his own newness in the community, and all the other obstacles facing this group of 13 immigrants, the program had been a success. And this was only the beginning.

The Leadership Academy for Immigrants has since graduated students in two cohorts — one in Tucson, and a binational group from Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico.

Its mission is to "promote the individual development of immigrants for a faster and better integration, and increased participation in leadership roles, and serving as a principal education and networking resource for advocacy on issues affecting their communities."

Among the many accomplishments of the class of Tucson is the creation of the Native People from Latin America’s council, known as Xajun Ulew (“One World” in Maya K’iche). Xajun Ulew remains active in the Tucson community, running a community garden for medicinal herbs as well as various cultural events.

Among the accomplishments of the class of Nogales is the creation of the binational Nogales Community Center, the first binational community center in the area. Residents of Nogales, Mexico, and Nogales, Arizona are able to visit the center for free cultural, social and wellness activities.

CLINIC would like to express its gratitude to Ricardo Morales Bermúdez for taking the time to share his story, and to Chicanos Por La Causa. You can learn more about Chicanos Por La Causa here.

You can learn more about the National Immigrant Empowerment Project here.

This story was written by Kathleen Kollman Birch through interviews with Ricardo Morales.

To make a donation to support CLINIC's work, please click here.

CLINIC advocates for humane and just immigration policy. Its network of nonprofit immigration programs — over 450 organizations in 49 states and the District of Columbia — is the largest in the nation.